Surrounded by members of the National Space Council (NSC) at the U.S. Space and Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama, Vice President Mike Pence announced a new goal for NASA: Put American astronauts back on the surface of the Moon by 2024.

Echoes of President Kennedy’s 1962 “We choose to go to the Moon” speech, which the VP and head of the NSC referenced twice, seemed to fuel a sense of excitement at such an ambitious goal during his March 26 address, beginning the council's fifth meeting. “The rules and values of space, like every great frontier, will be written by those who have the courage to get there first and the commitment to stay,” Pence remarked.

“It is the stated policy of this administration and the United States of America to return American astronauts to the Moon within the next five years.”

Vice President Mike Pence speaks at the fifth meeting of the National Space Council.

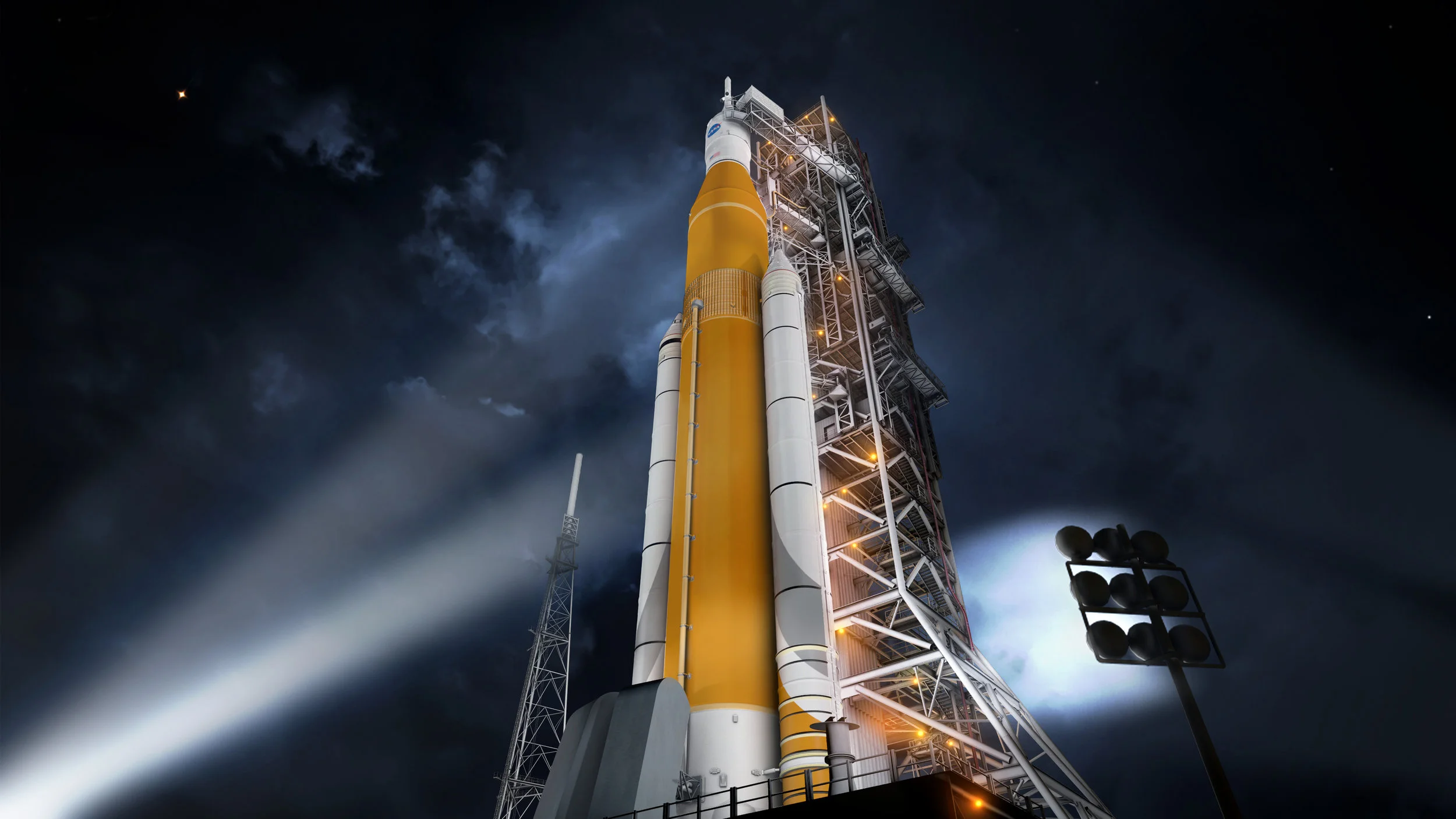

Pence went on during his address to emphasis that NASA’s aim to land humans on the Moon by 2028 was “just not good enough.” This comes less than two weeks after NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine told members at a Senate Commerce Committee hearing that the Space Launch System (SLS), the rocket NASA is relying on to establish a permanent lunar presence, would once again be delayed; this time, beyond its targeted maiden launch date in June 2020, sending Orion around the Moon for Exploration Mission-1 (EM-1).

Bridenstine, at that same hearing, revealed for the first time that NASA was considering the use of commercial rockets to stand in for SLS on EM-1, to prevent the 2020 launch date from slipping further. Pence in his NSC speech, stressing the agency proceed with “urgency” to meet this new goal, seemed to reinforce the administrator’s earlier remarks, saying, “we’re not committed to any one contractor… And if commercial rockets are the only way to get American astronauts to the Moon in the next five years, then commercial rockets it will be.”

Responding to VP Pence at the NSP meeting, Bridenstine seemed to double down on SLS and commented on NASA’s investigation into using commercial rockets for EM-1, stating commercial options weren’t viable. “If we want to achieve 2024, we have to have SLS. We have to accelerate its agenda,” Bridenstine said. He elaborated at a hearing the next day, saying, “We did look at those commercial options… We came to a determination that while some of those options are feasible, none of those options … are going to keep us within budget and on schedule."

Landing American astronauts on the Moon by 2024 includes the completion, at least in part, of NASA’s Lunar Gateway outpost — a permanent orbital station able to house astronauts long-term, with docking ports for Orion and a reusable lunar lander to ferry robotic and crewed missions to and from the Moon’s surface.

Artistic rendering of NASA's Lunar Gateway Station concept. Image credit: NASA

It is notable, regarding lunar landing sites, that Pence directed NASA to land on the Moon’s south pole, where water-ice permanently shadowed in the Moon’s craters can be mined and repurposed. In a process known as In-Situ-Resource-Utilization (ISRU), water-ice on the Moon can be broken down into its basic elements — hydrogen and oxygen — and converted into any number of resources from breathable air to rocket fuel. Perfecting this process is critical to a sustained human presence in deep-space, and NASA aims to use the Moon as proving ground.

Short of Orion’s Exploration Flight Test-1 (EFT-1) in 2014, none of these technologies or systems currently exist in space, and are at best only in their design or development stages down on Earth. In fact, the Trump Administration’s FY2020 budget proposal for NASA originally suggested deferring development of the SLS Block 1B Exploration Upper Stage (EUS), which has been touted as the only rocket capable of launching necessary Lunar Gateway modules into orbit of the Moon.

A day after the NSC meeting, Bridenstine found himself fielding questions at NASA’s FY2020 budget request hearing before the House Appropriations Committee. He outlined the steps and hardware necessary for NASA to make Moon 2024 a reality. Bridenstine mentioned a new 45-day study undertaken by NASA to determine the best ways to ensure SLS launches on time without increasing cost.

"If we're going to have boots on the moon by 2024, as the vice president indicated yesterday, which I believe we can achieve, we're going to need SLS. We're going to need to accelerate it and get as many of those [rockets] as soon as possible, and we're going to need Exploration Upper Stage as soon as possible.”

Bridenstine recommitted NASA to launching Orion’s EM-1 using an SLS rocket, and assured committee members the vehicle would meet its June 2020 target. Following that, and the completion of the EUS, the administrator outlined the need for an SLS launch every six months in order to achieve the Moon 2024 goal.

“We’ve got to have a big rocket. That’s what SLS is. What the Exploration Upper Stage allows us to do is put even more mass into orbit around the moon, and ultimately get to a day when we can co-manifest payloads. In other words, we can launch hardware that would include a lander, it would include habitation, and include the Orion crew capsule and the European Service Module all at the same time. So if we want to accelerate to get to the Moon as soon as possible, the SLS is a critical piece of that, and so is the Exploration Upper Stage.”

For a program that has suffered over a decade of delays, cancelations, repurposings, and redesigns, five years seems like a fast turn around to commit a rocket — which has never flown once — to launch twice a year and establish a permanent lunar outpost. If SLS, which emerged from the ashes of the canceled Constellation program (2005-2010), manages to launch by 2020, it will do so at a total cost of nearly $50 billion from the beginning of NASA’s deep-space efforts and the Constellation program.

Though, for all its setbacks, SLS has certainly accomplished one thing: creating jobs. The widespread production of the SLS rocket and its components at NASA facilities across the United States has created tens of thousands of jobs; more than 13,000 in Alabama alone. Representatives at the March 27 House Appropriations Committee hearing, particularly those from districts effected by the success or failure of SLS, seemed to stress this when applauding Bridenstine’s assurance that SLS production would have to be scaled up, not down, if NASA is to meet Pence’s Moon 2024 goal.

Rep. José Serrano (D-N.Y.), Chairman of the committee, began the hearing emphasizing that the political nature of of an accelerated SLS schedule was not lost on the group, stating that a June 2020 launch date was looking “more and more like a political deadline.” He went on to say, “as you well know, seventy-five percent of our profession is perception. And the perception by many is that [SLS] is being accelerated so it can come and excite the country a few months before a November [election] that’s going to happen in 2020. Understand that’s out there for people to talk about.”

Still, SLS concerns aside, when Pence addressed the challenges ahead for NASA, he insisted the agency “must transform itself into a leaner, more accountable, and more agile agency” in order to meet the Moon 2024 goal. Despite an apparent commitment to SLS, there still may be commercial options.

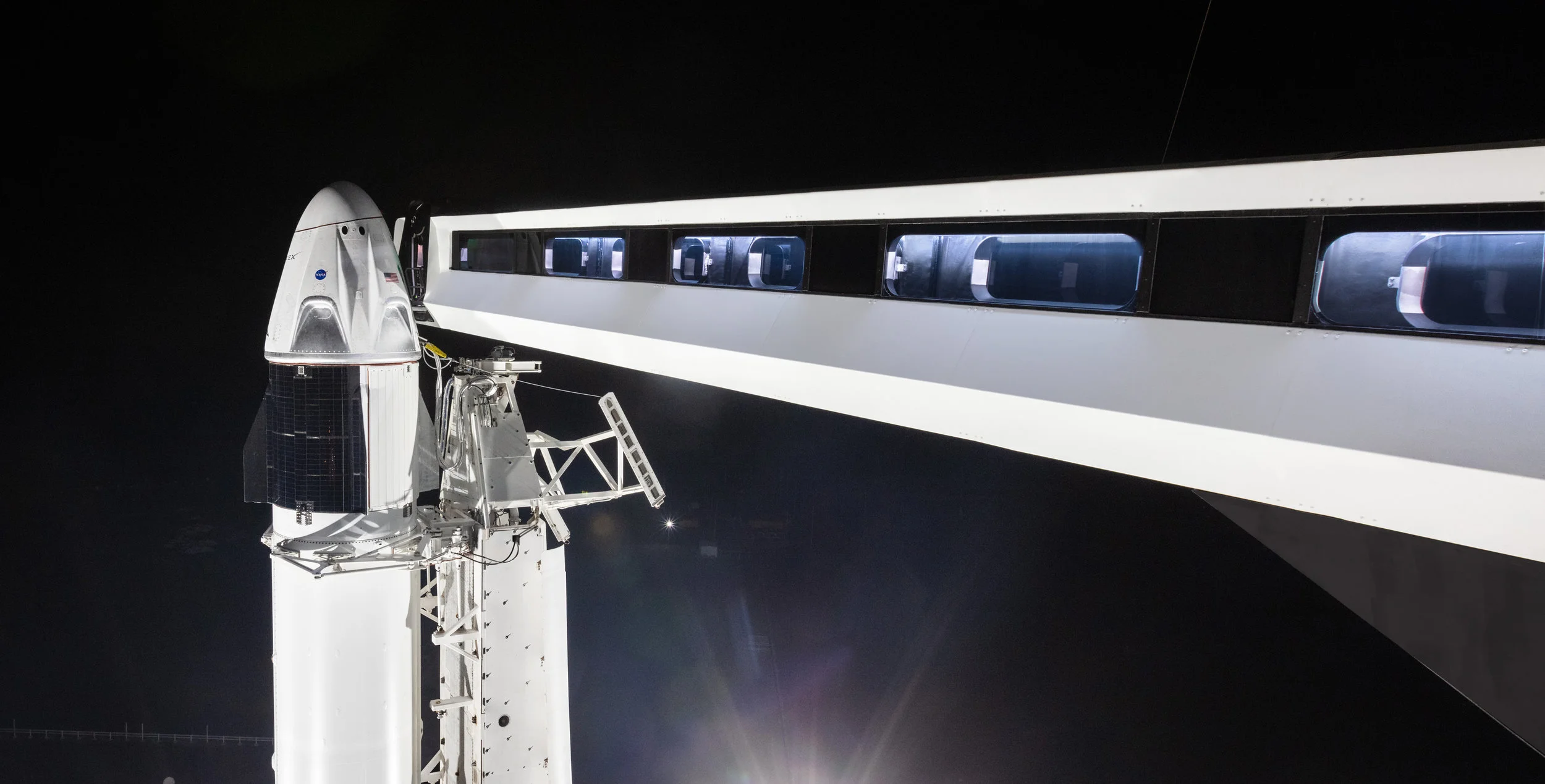

Elon Musk’s SpaceX is currently building its own super heavy lift rocket, Starship. Initially unveiled as the “BFR” in September 2017, the private space company boasts the rocket will be able to lift 100 tons in payload to low-Earth orbit (LEO). A miniature version of SpaceX’s Starship is currently undergoing development at the company’s Boca Chica, Texas facility, and is expected to start sub-orbital test flights this year. Musk plans for SpaceX to launch Starship around with moon in 2023 with the world's first private lunar passenger.

A leg up for SpaceX’s Starship compared to SLS, other than already having a physical test vehicle with actual rocket engines attached, is its ability to land. While the SLS rocket and the Orion capsule undergo further development for EM-1, there is still no answer as to how astronauts will actually land on the moon.

NASA published a Request for Information(RFI) in 2018 regarding the availability of lunar payload delivery services, and selected nine eligible companies to bid on Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) contracts. However, the RFI has no mention of landers capable of transporting human crews. So, at this point, the only lunar lander designs available to astronauts are those in artistic renderings.

Artistic rendering of a lunar lander concept for NASA's deep-space program and a return to the Moon. Image credit: NASA