SpaceX’s Crew Dragon spacecraft completed an Atlantic Ocean splashdown this morning, Friday March 8, at 8:45am EST, about 230 miles (~370 kilometers) east of Cape Canaveral. The spacecraft’s hatch was closed yesterday at 12:25pm EST, March 7, and undocked from the station at 2:32am EST this morning. Following a 15 minute deorbit burn at 7:54am EST, and a successful parachute deployment, Crew Dragon was recovered by SpaceX’s Go Searcher recovery ship to make its way back to Port Canaveral.

SpaceX hopes to soon use Crew Dragon to send humans into low earth orbit (LEO). The Demonstration-1, or Demo-1 (DM-1) mission docked the capsule to the International Space Station (ISS) for a relatively short stay - less than a week.

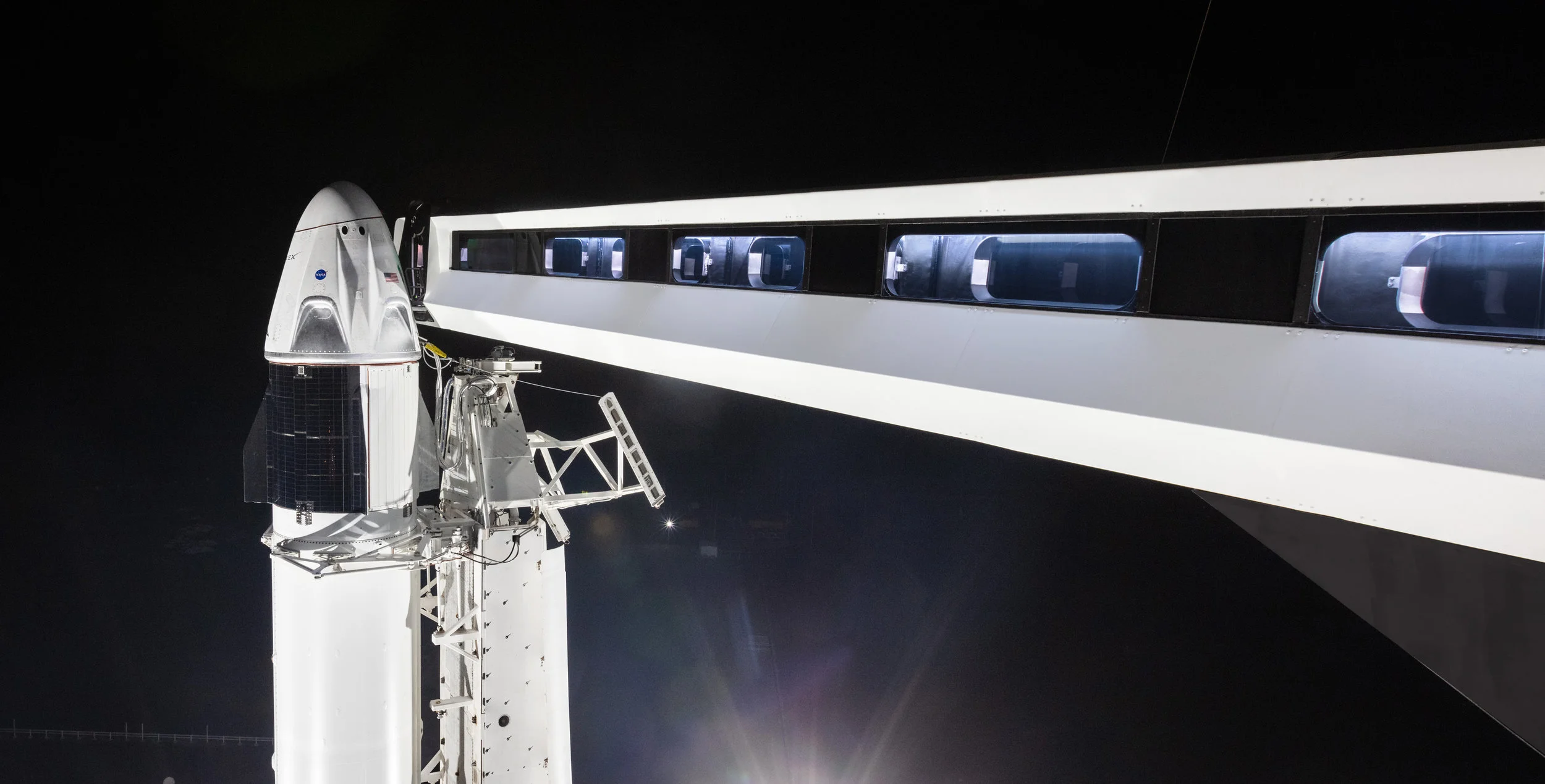

Launched from Launch Complex-39A – the same launch pad that hosted the departure of Earth’s first moon walkers aboard Apollo 11, as well as dozens of space shuttle missions – a newly redesigned Falcon 9 Block 5 rocket lifted Crew Dragon into orbit for a quick 27 hour trip to the ISS.

Falcon 9 Block 5 lifts off from LC-39A carrying Crew Dragon to orbit. Image credit: NASA

The second of SpaceX’s Florida-based launch complexes, the company began launching rockets from historic LC-39A in 2017. Since then, crews have worked to convert the facility to accommodate SpaceX’s future plans, including those involving the company’s interplanetary vessel, Starship. As a result, the launch site has been stripped of much of its shuttle-era infrastructure. In August, SpaceX’s sleek new crew access arm was installed, and the tower has since been painted black.

Launches can sometimes take up to five days to rendezvous with the ISS, given the orbital inclination of the station and the plane into which a rocket launches. Thanks to an early morning alignment of the station with the Kennedy Space Center, Crew Dragon lifted off at 2:49am Saturday, March 2, and took just over a day to intercept humanity’s orbital outpost.

Crew Dragon’s mission marks a number of significant milestones for SpaceX, and for NASA. Fully autonomous, Crew Dragon mimics its predecessor, the Dragon cargo capsule, in design, but is, at its core, a brand new spaceship.

This is SpaceX’s first spacecraft to fly with functional displays and navigation controls, seats, and a life-support system capable of sustaining astronauts and cargo to the space station and back.

To help demonstrate the capsule’s life support system effectiveness, as well as a myriad of other in-flight measurements, SpaceX strapped a spacesuit-clad dummy named Ripley (after Sigourney Weaver’s character in the “Alien” movies) into one of Crew Dragon’s seven seats to go along for the ride. Hans Koenigsmann, SpaceX’s Vice President of Build and Flight Reliability, doesn’t quite like calling it a “dummy,” though, when asked at a Kennedy Space Center briefing a week before launch.

Anthropomorphic Test Device, “Ripley” sits aboard Crew Dragon awaiting liftoff. Image credit: SpaceX

Similar to the famous Starman mannequin seated in Elon Musk’s old Tesla Roadster, which launched aboard SpaceX’s first Falcon Heavy last year, the Anthropomorphic Test Device, or ATD, aboard Crew Dragon is, in fact, pretty smart. The ATD is fitted with sensors throughout its suit and body to measure atmospheric and environmental data to learn exactly what astronauts will experience when they launch on a crewed mission later this year. “It will measure forces, acceleration, and the environment itself," Koenigsmann said at the briefing.

DM-1 also serves as a test for the spacecraft’s new systems. Compared to its cargo-focused predecessor, Crew Dragon features a redesigned power system with solar panels integrated into the body of Dragon’s trunk, an upgraded cooling system, and eight SuperDraco thrusters built into the capsule.

Image credit: SpaceX

Unlike the Dragon cargo spacecrafts, which have to be captured by the station’s robotic arm and maneuvered into place to be berthed to the station, software aboard Crew Dragon uses lasers and sensors to dock with the ISS automatically. The International Docking Adapter (IDA-2) attached to the forward facing Pressurized Mating Adapter (PMA) on ISS’s Harmony module, delivered by SpaceX’s CRS-9 mission in 2016, allowed Crew Dragon to demonstrate its autonomous docking capabilities.

“We need to make sure that [Crew Dragon] can safely go rendezvous and dock with the space station, and undock safely, and not pose a hazard to the International Space Station.”

At 5:51 am EST on Sunday, March 3 (ahead of schedule), while the space station was in orbit above Australia and New Zealand, NASA astronaut Anne McClain confirmed soft capture with the Crew Dragon, making it the first commercially operated spacecraft capable of carrying people to dock with the International Space Station. After opening the hatch, McClain, along with Canadian astronaut David Saint-Jacques, and Russian cosmonaut Oleg Kononenko performed a short welcoming ceremony to honor the occasion.

Crew Dragon docked with ISS. Image credit: NASA

The completion of DM-1 brings SpaceX to a significant checkpoint in the company’s efforts to launch people into space, and furthers their certification process with NASA as the agency considers whether to deem Crew Dragon space-worthy and safe to ferry regular crew rotations to the ISS. Koenigsmann stressed this at last week’s briefing saying, “Human spaceflight is the core mission of SpaceX, so we are really excited to do this. There is nothing more important for us than this endeavor. We really appreciate the opportunity from NASA to really do this and have a chance to fly up to the station.”

“Today’s successful re-entry and recovery of the Crew Dragon capsule after its first mission to the International Space Station marked another important milestone in the future of human spaceflight... Our Commercial Crew Program is one step closer to launching American astronauts on American rockets from American soil. I am proud of the great work that has been done to get us to this point.”

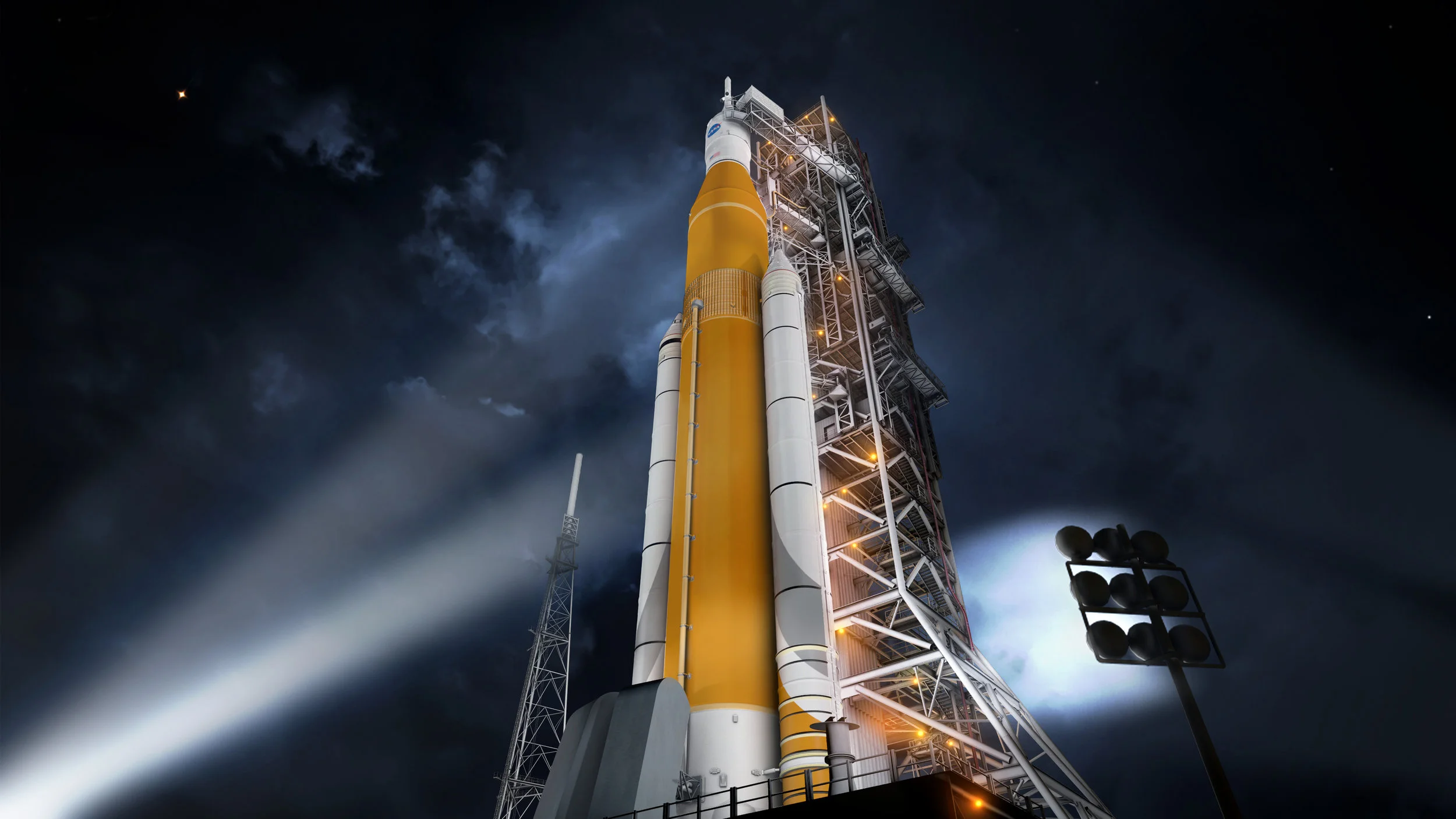

SpaceX is on course to launch astronauts from American soil for the first time since the final Space Shuttle launch, which occurred from the same LC-39A launchpad, when Atlantis lifted off for its final flight in July, 2011. In 2010, as the shuttle-era was coming to a close, NASA partnered with a number of aerospace companies to develop new commercial crew vehicles. In 2014 the agency awarded SpaceX and Boeing $2.6 billion and $4.2 billion contracts, respectively, to complete their human-rated Crew Dragon and CST-100 Starliner capsules to fly astronauts to the International Space Station.

Digital rendering of Starliner and Crew Dragon with the ISS. Image credit: NASA

Since the retirement of the space shuttle, and throughout the development of its Commercial Crew Program, NASA has relied on the only crew-rated vehicle currently in operation, Russian-built Soyuz spacecrafts, to carry astronauts to and from the ISS, costing the agency $81 million per seat. Seats aboard SpaceX and Boeing vehicles are estimated to cost only $58 million.

Once awarded the Commercial Crew contract for Crew Dragon, SpaceX set an aggressive goal to launch an unpiloted DM-1 by the end of 2016, with NASA’s hope to start flying crews as early as 2017. Not atypical for any NASA project, and certainly on par for SpaceX, safety concerns and vehicle redesigns (and finally, the most recent government shutdown) continually pushed the DM-1 launch date back.

Requirements for both SpaceX and Boeing dictate the companies prove a 1 in 270 chance of an in-flight catastrophe with a loss of all crew members. NASA’s ISS Crew Transportation and Services Requirements Document mandates that 99.73 percent of Commercial Crew missions keep astronauts safe during their ascent to space, compared to the space shuttle, which came with a 1 in 80 chance of loss of life.

One delay came when the SpaceX CEO Elon Musk announced a change to Crew Dragon’s landing systems. Utilizing the capsule’s eight SuperDraco thrusters, and legs that extended from the heat shield, Crew Dragon was originally designed for propulsive landings on land, similar to how SpaceX lands its first-stage Falcon 9 rocket boosters. In July, 2017, citing NASA’s safety requirements and concerns, which seemed to echo from the days of the space shuttle’s heat shield issues, Crew Dragon was redesigned to return to Earth Apollo-style, and use parachutes to land the capsule in the ocean. The landing-legs were nixed.

As part of the Crew Dragon’s human-rated certification process, NASA is hoping to use today’s successful parachute deployment to further qualify the system for crewed flights. While propulsive landings were cut from Crew Dragon’s design, the capsule’s SuperDraco thrusters were not. Following a successful demonstration in 2015, SpaceX plans to reuse to the DM-1 Crew Dragon for a pad abort test this June to verify the thrusters’ ability to propel astronauts away from a failing rocket as part of an emergency abort system.

Crew Dragon pad abort test, 2015. Image credit: SpaceX

A report published in January, 2018 by the Government Accountability Office (GAO), which periodically audits NASA projects, estimated that SpaceX wouldn’t be certified to fly astronauts to the ISS until December 2019, and that Boeing’s certification would likely be delayed until February 2020. The success of DM-1 seems to indicate a faster timeline, however. DM-2, the second Crew Dragon test flight, to include two NASA astronauts on board, is planned as soon as July, while Boeing is targeting an unpiloted test of its Starliner capsule no earlier than April. This would put Starliner on track for a three-person test flight sometime in August.

(left to right) NASA Astronauts Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley. Image credit: SpaceX

Veteran NASA Astronauts Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley are assigned for SpaceX’s DM-2 mission. They will spend two weeks in orbit aboard the ISS, conducting various tests on the Crew Dragon vehicle. Behnken and Hurley will splash down and be recovered in the Atlantic by Go Searcher, the same way today’s DM-1 capsule was retrieved.

Given the success of the Crew Dragon capsule, SpaceX hopes to retire its first generation cargo vehicle next year, and exclusively transport both crew and supplies aboard the new vehicle. A decision on whether to certify Crew Dragon for regular crewed missions to the ISS will come from NASA only following the success of DM-2.